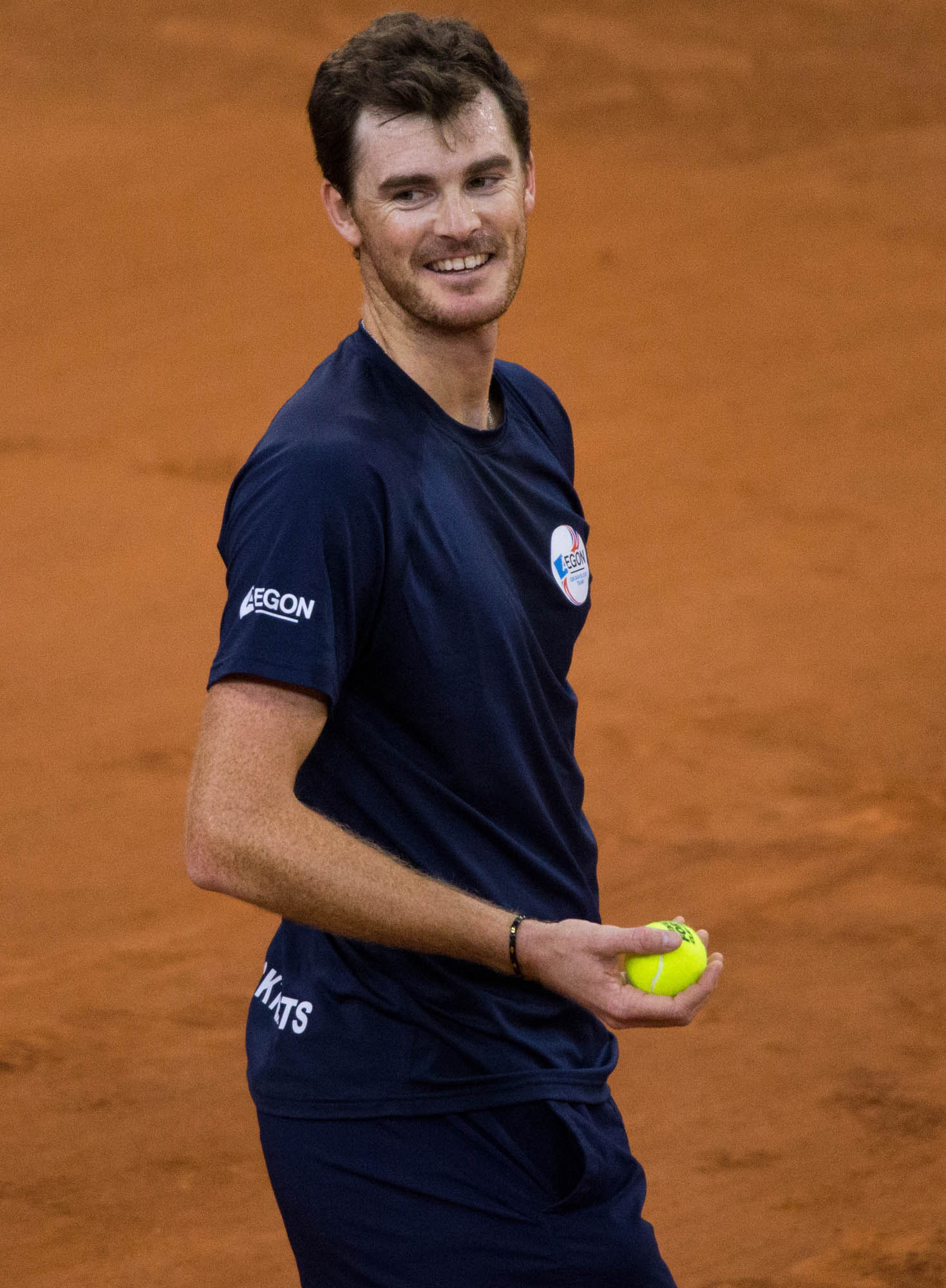

Tennis in the spring sunshine in Monte Carlo: sounds like bliss to most of us, but it’s just the day job for Jamie Murray, one of Britain’s most successful tennis players ever. That’s where we talk to Murray, the former doubles world No 1, five-time Grand Slam champion, three-time Olympian and British Davis Cup winner. It’s a glittering career, but since the media spotlight has always shone most brightly on the singles game, it’s not one that’s been celebrated nearly enough.

The 6’3”, 32-year-old has been on the ATP tour for nearly 15 years now, so life has largely been lived on the road. When people watch the pomp and ceremony of the Wimbledon finals, they often forget about the year-round gruelling flying, waiting, training and recovering that make up real life as a tennis player. “It’s like a travelling circus,” says Murray in his soft Scottish burr. “You’re moving from tournament to tournament, and it’s the same people you’re seeing every week.” He won’t be drawn on behind-the-scenes dramas and bitchiness, but says that players largely stick to their own camps of coaches and physios. “The doubles guys in general are more social than the singles players – we tend to be a bit more pally.”

It’s a suspended childhood in many ways, hopping from tournament to tournament in your sports kit, with your racket bag slung over your shoulder, whiling away the time between matches as best you can (Murray’s current distractions include Netflix, his Kindle and games of chess on his phone). Of course, now there are fatter cheques, starrier hotels and more glamorous locations, but it’s essentially the same thing he’s been doing since he was an internationally ranked 10-year-old.

Murray is away from his Colombian wife, Alejandra (neé Gutiérrez), and his London home for around 30 weeks of the year. He credits her with helping him regain focus on his game around the time when they met in 2009. “She helped me a lot with my tennis. At the start, she didn’t travel that much and then she started to travel a lot, and now she’s fed up with it. She still comes a bit, but it can be really boring because it’s a lot of hanging around. A lot of the time, they’re just waiting around for you in player lounges. It’s a lot of sacrifice. I don’t think it’s her first choice to travel the world as a tennis player’s wife!” Murray admits it’s not easy maintaining relationships on tour (just imagine being Federer, with four children in the entourage, too), but Alejandra joins him for choice tournaments, Monte Carlo being one.

At 32, he might have been at retirement age by now, but because of improved fitness, nutrition and treatments, many players are pushing through into their 40s, like the doubles duo the Bryan brothers (Bob and Mike have won 23 and 20 Grand Slam doubles respectively and spent most of their careers at the top). “They’re the greatest team ever – there’s no arguments about that,” Murray says. “Every time the Bryans step on the court, they know that the other team are desperate to beat them, so for me it’s incredible that they were able to be so dominant. They’ve done so much for doubles in promoting the sport and getting it the exposure it badly needed the last few years.”

The right kind of recognition for doubles seems to be at the forefront of Murray’s mind. Since most club-level tennis is played in pairs, it’s curious that, professionally, it isn’t more popular. New ways of sharing the sport through social media and greater participation from a red-hot new generation of stars suggests doubles is about to undergo a transformation. The Instagram accounts of Functional Tennis, Tennis TV and the US Open are filling feeds around the world with outstanding rallies, many of them from nail-bitingly good doubles matches. It’s helping awaken people to the extraordinary skill, speed and teamwork of the game. “It’s a chance for us to show some of the exciting points and the crazy things that happen on a doubles court, and get people engaged and interested in coming to watch.”

Encouragingly, the new crop of tennis talent, including Canadian Denis Shapovalov and South Korean Chung Hyeon, have been playing doubles as well as singles at recent tournaments. It’s not something you’d have seen from a young Djokovic or Nadal – so why is this generation more keen to engage? “Because the money is good and with the scoring format on tour, there’s no endurance to it. You’re playing matches for between an hour and an hour and a half really, so it’s not super-demanding. For the younger guys, it’s great for them to play doubles because it helps them develop their game, especially at the net. Guys playing singles never want to come forward and when they do, they just look really uncomfortable, so doubles hones their skills and teaches them new things. They’re young as well, so it’s easy for them to play two or three hours a day, no problem.”

Murray still thinks doubles could be appreciated more. If broadcasters showed more of their matches during peak viewing times, people would start to see that as well as the impressive, gladiatorial slogging of singles, doubles can be the height of sports entertainment, too. “Doubles players could be stars as well if the game was promoted better,” says Murray. “I’ve been on the ATP for a couple of years, and we’ve been really trying to work with the tournaments to do a better job of that, but it takes time. I think it’s starting to move in the right direction, but of course it could be way better than it currently is.”

Murray has had over 50 doubles partners over his career, with his main ones being Bruno Soares, John Peers and Martina Hingis. But the public’s interest is always piqued when he has to play with his brother, Andy, usually at the Olympics or in a Davis Cup tie. Whilst Andy has had far greater singles success, Jamie is the far better doubles player, and it’s sweet to see the older of the brothers squirming and stalling out of fraternal loyalty when asked about their partnership.

The repeated pauses, retractions, likes and buts speak for themselves: “On court, like, it’s … I mean, we’re a lot better now than probably when we were at 15 or 16 years old … but it’s different because obviously I’m used to playing with Bruno and we play doubles all the time, so we’re kind of … ” Jamie trails off. “Whereas with Andy, it’s always different, you know, and it’s a different kind of skill set in a way, so you know, like we have to manage that as well. And he has a lot of amazing skills for doubles, but because he’s not really playing that much, sometimes it will take him a little while to get into the swing of things, so we have to, like, work at that and manage that as best we can. But we’ve played some amazing matches together.” What Jamie is humbly trying to get across is that, yes he’s definitely better than Andy at doubles!

If the Bryan brothers are anything to go by, Jamie Murray could be on tour for eight more years. But if he does decide to hang up the rackets, what next? How does a professional sportsman possibly find something to match up to the intensity of the training, the adrenalin of the game and all those adoring crowds? Of course, many of them don’t, falling into depression, alcoholism or bit-part commentary, but there’s a square head on Jamie Murray’s shoulders. He says he’d love to help Scottish juniors, but he’d also be a major asset for the ATP with his knowledge as a player, all-round likability and undimmed passion for the game.

As well as talking about greater prominence for doubles, he’s thoughtful about how the game might change in the era of social media, whether doubles needs to be sped up with shorter changeovers and whether singles matches should be shortened at the Slams (Billie Jean King suggested men should no longer play five-set matches). “The game is probably as physical as it’s ever been. Over the last 10 years, there’s been some brutal matches, and the tennis schedule is pretty relentless from January to November. Grand Slams have always been five sets, and it’s the ultimate challenge, but do the next generation of fans want to sit and watch tennis for five, six, or even three or four hours? I think people’s attention spans these days, with smartphones and all that stuff, are just getting less and less. I think that’s something that tennis needs to look at if it really wants to capture the next set of fans.”